8. how to get around

The transportation network is quite thorough in Southeast Asia, although this doesn't necessarily mean it's either good or comfortable. In general, if you look on your map and see some town on a road or river that you would like to go to, the chances are that you will be able to get there by public transport if you just ask around at the bus station, market and guest houses.

Most people in these countries do not have their own personal car or boat, so to get around they need some form of cheap public transport. On land this will generally be some variation of what we would call a "bus", but in reality it comes in all sorts of shapes and forms, among them mini-van, pick-up truck, tractor, or anything you could imagine with four wheels that can hold a lot of stuff. For river transport, ferries, speedboats, cargo boats, longboats and one man dinghies all do the job.

In Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei and Thailand there are large, comfortable, air-con buses available for all the major routes on all the major highways. For cross-country trips, these are often the best way to go, both for price and comfort. There are generally less comfortable, non air-con buses (kind of like old school buses in the US) that ply between smaller towns along the route, but the net fare is rarely less than the single air-con ticket. Of course, if you have a lot of time on your hands, you shouldn't be making cross-country bus trips at all, since you're missing everything in between. Short hops on sub-par buses are great ways to get away from the tourist track and meet locals. The bigger cities all have several bus stations, usually one for each geographical direction or major highway leaving the city, so ask around beforehand to make sure you go to the right one.

In the less-developed countries, the transport situation is entirely different. Burma has a few large, air-con buses that run from Yangon to Mandalay and Taunggyi (Inle Lake), but these are catered to tourists and wealthier Burmese, so should be avoided at all costs. The larger towns (Yangon, Mandalay, Pathein, Bagan) have several bus parks, often located near the larger outdoor markets. Ask at your guest house which bus park you should go to for your desired destination. Almost invariably, transportation to places more than a couple hours away will leave very early in the morning (5-7am). If you miss it, you will have to wait until the next day, or settle for a closer destination. When you finally find the vehicle that is going where you want to go, grab a seat early so you don't have to sit on the roof or hang off the back. If there are a lot of women getting on, men should give up their seat, as the Burmese men do. In these situations, do what other people your age and sex seem to be doing. The fare is generally set, and you'll often pay before you ride, getting a small receipt in return. Occasionally, especially around touristy Bagan, Mandalay and Pyin U Lwin, you will come across "white manís fares." If you catch them doing this (by asking locals beforehand and watching what others are paying), protest, get off, and go to another bus. There is plenty of competition, so you donít need to pay more than you should.

Overloaded "bus" in Burma...

In Laos the situation is quite similar. Show up at the bus park early in the morning (not quite as early as Burma -- more like 7-8am) and follow the same rules as above. Bus parks in Laos are usually located next to the market. If you're trying to travel between Vientiane, Vang Vieng and Luang Prabang, and your guest house man says he has a bus going there, be skeptical. There's a good chance that this is a tourist bus, with no locals on board, that will do nothing to increase your understanding of Laos except possibly to learn where the cheapest opium is. Remember, the locals have to get there somehow, and this bus obviously isn't it. Ask around at the market and you'll find it.

... a busted one in Laos...

Cambodia has the roughest transport in Southeast Asia. Away from greater Phnom Penh, all road travel is in the back of pick-up trucks. Show up at the market in the morning (6-8am) to find your pick-up. Competition is intense, so if a bunch of guys run up to you and grab your bag, play along. They're trying to get you to ride their pick-up (so they can fill it up earlier, leave earlier and begin the return journey earlier to make money faster), so use these guys to your advantage. Just tell them where you're going and they'll steer you the right way. Sit in the back for the cheapest and most interesting ride, sit up front if you want to pay twice as much. Buy a scarf ("kroma") to keep off sun and dust, as you'll notice everyone else does. These cost about 60 cents and make a great souvenir, besides greatly improving your comfort in the back. Finally, hold on, because the drivers are not known for driving slowly. Prices are generally fixed, but if in doubt ask around beforehand to see what the price should be. You can also look at what other people are paying to make sure you get charged the same amount. From Phnom Penh, comfortable air-con buses radiate out to Sihanoukville, Kampong Chnnang, Takeo and points in between. Minibuses run to Kampong Cham (much cheaper than speedboat).

... and in Cambodia.

How to wear a "kroma."

Good highways in Thailand and peninsular Malaysia have phased boat travel out, but in the less-developed regions of Burma, Laos, Cambodia, Sarawak and Sabah, river travel can be a slow, peacful way to get off the beaten path. Travel along the Mekong in Laos and Cambodia, the Rejang in Sarawak, and the Ayeyarwady in Burma are all popular among travelers. As mentioned above, if there is no highway going to a certain town, then the locals must get there by boat. Service is often infrequent or sporadic, but a good general rule is to ask around at the docks the day before you want to travel. Usually long distance river "ferries" will leave early in the morning.

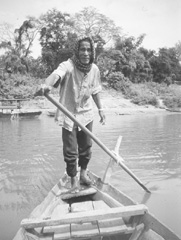

Heading upriver, by motorboat...

... and by slow-boat (Cambodia).

Trains are an interesting, cheap, but slow alternative to road transport. In Thailand, Malaysia and India, upper class sections are available with bunks and air-con, but these are expensive and uninteresting. Second and third class sections are cheaper than bus travel, and put you in touch with how the common people travel. You may not get much sleep, but then why are you traveling at night anyway? Food vendors walk through from time to time with an assortment of goodies, or you could buy food from hawkers that congregate at many train stops. If itís around dinner time and you notice a lot of people on the train are buying rice, itís probably a good idea to do the same, since they may know something which you donít (such as this being the last rice stop for some time).

In Cambodia the train between Battambang and Phnom Penh is technically free of charge to foreigners (as of Feb. '99) since the government does not want to sell tickets to you and hence be responsible for your safety on a train which historically has been subject to derailment, land mines and Khmer Rouge attacks. In 1994 three foreign backpackers were abducted on the train, taken to the mountains, and killed. In the town of Bamnak in Pursat Province, Khmer Rouge guerrillas once opened fire on the train, killing dozens of citizens. Since the Khmer Rouge defections in late 1998, I tend to believe that Cambodia is a much safer country than in the past, but this does not mean that bandits, rednecks and derailments don't occur any more. Itís up to you.

Grand Central Station (Battambang, Cambodia).

On a more local scale, bicycles can be a great way to toot around town or take short trips into the surrounding countryside, while keeping yourself fit. Bikes are usually of the sturdy, one-speed, pedal-brake, Chinese variety, and can frequently be rented from guest houses and other entrepreneurial locals for around $0.50-1.00 per day. Popular biking areas include Bagan, Mandalay and Ngapali, Myanmar, and Vang Vieng and Muang Sing, Laos. In other places, if youíre thinking that it would be nice if you had a bike to get around, chances are that other tourists have felt that way too, and bikes will be available if you ask around. The guest house guys are the best people to ask about this.

Serious bikers have been known to ride all the way from Europe to West Africa and SE Asia. If this is your cup of tea, go for it! The few bikers I met reported that they rarely had problems finding food and accommodation when they were in the countryside, since locals tend to treat long-distance bikers and backpackers alike with great hospitality and care. See also 10. how to meet locals.

Bikes are the best way to go in Bagan (Myanmar).

The oldest and cheapest form of transport is always an option, but in SE Asia it is rarely practical as a means of covering large distances. Trekking has become quite popular and commercialized between various hill tribe villages in northern Thailand and in the many national parks of Malaysia, but itís safe to say that the mountains of Nepal remain the only places in South/SE Asia where walking is essentially the only transport option available. Roads and automobiles do not exist in most of the country, and consequently an extensive footpath network has developed over the eons connecting adjacent villages. These trails serve as the interstate highways of Nepal, where porters (truckers), villagers and tourists interact. Trekking in Nepal, therefore, is not a wilderness experience. You will rarely go more than a few minutes without meeting another person. Guides are not necessary since every villager on the trail knows the terrain quite well.

My purpose here is not to present a trekking guidebook. For more detailed information on trekking in Nepal, see the travel section of your local bookstore or library.

On the trail in Nepal (yes, thatís Everest).

Since transport is so cheap in SE Asia itís not necessary to work your way around by hitch-hiking, even if youíre on a tight budget, as it is back home in the West. In the poorer countries of SE Asia (Indochina and Burma), almost nobody has their own private vehicle, so your chances of being picked up by some generous local are slim.

If youíre standing on the side of the road with or without your thumb up, looking like you want a ride, you can bet that the next public transport to come along will consider you fair game. Outside of the big cities none of these countries have formal bus stations as we know it, so getting a ride from one town to the next is just a matter of waiting by the side of the road and hoping something will come along soon. This, like a lot of things in the third world, requires a lot of patience. Therefore, if youíre pressed for time and want to get somewhere soon, or if you want to make a short hop to some ruins or a waterfall just outside town, youíll need to hire your own personal transport, such as an enterprising kid with a moped or a bored tuk-tuk/taxi driver. Inquire at your guest house, because other foreigners have probably done the same thing before.

Mopeds are serious business in much of the third world (Burkina Faso).

On the other hand, Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei have advanced economically far enough that a lot of citizens do have their own cars. Malaysia is especially well-known on the travelersí circuit as being a great place to hitch. Hitching opens a lot of opportunities that would otherwise not be available to the shoestring traveler, such as the ability to get somewhere quickly that public transport doesnít serve often, or the confidence that you can go somewhere without having to worry about whether your next ride back will be tonight or a week from now. For example, you definitely have to hitch if you plan on going to Jerudong Amusement Park in Brunei, since the last bus back to BSB is at 6pm, which is about when the park opens. Generally you wonít have to wait more than a few minutes before a very friendly local will pick you up who is happy to take you wherever you want to go. Express your gratitude, as always, with smiles and friendly chat, and insist that they not go too far out of their way for you.

Finally, air transport is available in every country from the capital city to most provincial capitals and sometimes more remote hamlets. Tickets are cheap (sometimes as little as $10 each way), but still much more expensive than ground transport. Every town with air service will have some ticket agent that can issue a ticket on the spot. Internal flights are all regulated, have set fees, and are rarely sold out. Malaysia and Burma are the only countries for which you should normally consider flying. In Malaysia you'll have to fly to Sabah and Sarawak from the peninsula, since there is no boat link in between. Johor Bahru is the cheapest connection. For Burma, you cannot enter the country overland, so you'll need to fly into Yangon. If you're staying in Southeast Asia, it's cheapest to fly roundtrip from Bangkok (Thai Airways or Myanmar Airlines), or if you're connecting with South Asia, consider Biman (Bangladesh) Airlines for a Bangkok-Yangon-Dhaka ticket, or Air India for a Bangkok-Yangon-Calcutta ticket.

Biman Airlies Ė your friend in the skies.

Inevitably you will have occasions when you need to get somewhere quickly, when you donít feel like trying to figure out the local city bus network, or when you need to carry a lot of stuff. In these situations you need to hire transport. Back home this would be called a taxi, but on the road in the third world there are many different varieties, depending on the country youíre in, how far you need to go, and how much youíre willing to pay. Generally a normal automobile taxi will be available, cheap by Western standards, but expensive compared with the alternatives.

The most famous of all Asian hired transport is the bicycle rickshaw of the Indian subcontinent. The streets of Delhi or Dhaka can be so congested with rickshaws that you will find yourself sitting in rickshaw gridlock at times! The rickshaw is a three-wheeled cycle. The "driver" pedals up front, as on a bicycle, and the paying passengers sit on a narrow cushioned seat in the back. Up to four people can ride at a time, depending on the driverís strength and the agreed upon price. On hills he may get out and push. Since most rickshaw drivers come from the poorest of social classes, often eating just once per day, itís best not to expect him to be superhuman. Rickshaws are cheap (no more than 25 cents for up to a 15 minute ride) and consequently they are utilized by everyone. Always agree on a price before you get on.

The rickshaw capital of the world (Dhaka, Bangladesh).

The 1990s have seen the rapid growth in popularity on the subcontinent of the "auto-rickshaw," a three-wheeled buggy powered by a small engine. Most of these are of the black and yellow Indian "Bajaj" variety. In general auto-rickshaws are slightly more expensive than cycle rickshaws (25-50%), but much faster. Sounds great? The problem is that, like many things on the subcontinent, exhaust emissions from the auto-rickshaw are not regulated, and street-level air quality has plummeted to sub-Mexico City standards. Youíll find it quite repugnant to be in a swarm of these on the street for any length of time. Things may change, in fact Nepal has recently passed legislation regulating them on the streets of Kathmandu, but all I can recommend is that you breath through your shirt and try not to ride them too much.

In SE Asia variants of the rickshaw do exist, such as the sidecar trishaw in Burma or the front-car cyclo in Cambodia, but, as with the Indian variety, these are rapidly being phased out by modernization. In Thailand the "tuk-tuk" and in Laos the "jumbo", both a la auto-rickshaw, are now prevalent. In Cambodia the moped (called "moto" or "motorbike") has developed into a very practical means of transport. Sit behind the driver and hold on to the back of the seat. Short hops cost 500-1000r, with longer hauls going for roughly $2-3/hour.

Often times the best compromise between being cheap by walking and spending too much for a taxi is by the local "bus" network. You can bet that every decent sized town (the ones that are just a bit too big to walk across) will have one. Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur and Singapore all have modern networks. In the poorer countries, however, these arenít really buses, but more like minivans, pick-ups or even just cars that run a fixed route, dropping off and picking up passengers as they go. They can run in comfort and safety from the quite comfortable "minis" in Kota Kinabalu, to the clumsy and spartan "colectivos" of Mexico, to the atrociously sardine-packed "tro-tros" in Ghana. Yangon has a thorough system of pick-ups that cost only 2-3 cents per ride! These networks donít usually have maps or stable schedules, so the best way to figure them out is to simply ask around and try them out.

Before you head out from home, this question is likely to pop into your head, especially if you plan on hitting more than one continent. The answer is simple: it depends on how much time you have. Ideally you have lots of time to spare, so flying should be out of the question except to cross the big blue seas or to get to some hard to reach places (see above). The reason here is that flying prevents you from linking the big picture together. You miss everything you fly over. I grew up in a car traveling family in southern California, and for the longest time I felt that I had a good comprehension of how the southwestern US was linked together, in a physical and societal sense. But when I started jetting all over the place in college, I immediately felt that something was missing. Flying and Interstate highway driving are cheating Ė you donít really know a place well until youíve traveled there by the slow road. All quick-dip tourists you meet will tell you they wish they had more time to enjoy everything. Use this to your advantage, and youíll come out ahead in terms of what youíve gained from your trip.

The view can be nice from the slow road (Nepal).

On the other hand, the less time you have, and the greater the distance you want to cover, the higher the chances that flying will be a good idea. Letís say you have a three week holiday and want to "do" SE Asia. You want to see Bali, Singapore, Penang, Bangkok, Angkor and Saigon. Needless to say, this itinerary is quite ambitious, and definitely necessitates flying from Bali to Singapore, in addition to routing some ticket like Bangkok-Phnom Penh-Angkor-Phnom Penh-Saigon. Road, train and ferry transport are simply too slow and arduous to allow this itinerary. This example reinforces a key point to enjoyable travels: slow down (see 3. where to go). The above itinerary would make an ideal six month adventure.